Understanding and Managing Grief: When Healing Isn’t Linear

Loving and having someone or something important to you is an inevitable part of being human. So is the grief that follows when that beloved person, relationship, or chapter disappears from your life.

The heavy toll of loss can leave you wondering, “How long will this feeling last?” The truth is grief has no timetable and no deadline to meet. Grief is not a linear process or a set of boxes to check, it’s a whole-person response with repercussions that extend to the mind, body, and even other relationships.

What is grief?

Grief is a natural, multifaceted response to loss and significant life change. While commonly resulting from the death of a loved one, grief exists in spaces beyond this loss.

Other losses that can trigger grief include:

The end of a relationship

Being demoted, laid off, or fired from a job

Significant life transitions, like moving to a new place

The loss of a pet

Such losses can produce secondary losses, such as shifts in identity or social connection that compound the pain. A loved one’s passing or a divorce (primary losses) can cause lost contact with mutual friends and family members (secondary loss). For parents/guardians, a child’s death isn’t only a loss of what was but also a loss of what could’ve been.

While many people are familiar with the five stages of grief famously outlined by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in 1969, research now shows that grief rarely unfolds in neat order (Tyrrell, 2023). You may feel acceptance before anger, peace before sadness, or circle back to disbelief months later, all of which is entirely normal.

Modern grief theories emphasize that healing is non-linear. The Dual Process Model, for example, shows that people oscillate between focusing on the loss and re-engaging with life. The Continuing Bonds Model reminds us that maintaining an ongoing inner connection with the deceased can be part of healthy adaptation (Goodall, 2022).

How does grieving impact the brain and body?

A neuroimaging study by O’Connor and colleagues (2008) explored how the brains of people with complicated grief (CG) respond to reminders of a deceased loved one. Both individuals with CG and those with noncomplicated grief showed activation in brain regions associated with emotional pain—consistent with the distress of loss. However, only participants with CG showed activation in the nucleus accumbens, a region involved in reward and attachment.

This reward-related response was associated specifically with yearning, not with time since the death or general emotional distress. These findings suggest that in complicated grief, reminders of the deceased may continue to trigger the brain’s attachment-related reward pathways, which theoretically can make it harder to adapt to the reality of the loss in the present.

Mentally, grief may look like

Disbelief, forgetfulness, and disorientation

Persistent thoughts about how devastating and unfair your loss is

Persistent “if only” and “what if” scenarios

Negative self-talk about yourself and your future because of your loss

Difficulty imagining your life without the person, relationship, or thing you lost

Emotionally, grief may feel like

Numbness, emptiness, and lost purpose in life

Loneliness and disconnection

Rage or self-inflicted guilt that you could’ve prevented a loss but didn’t do enough

Desperation, helplessness, and hopelessness

Physically, grief could cause

Sensations that don’t feel right, like your body is frozen or wrapped tightly

Muscle tension you try to release by kicking, breaking, or pushing things

Lack of appetite

Restlessness that makes you constantly move around and pace

Lethargy and exhaustion that keep you in bed

What are the types of grief?

Grief takes many forms, each with its own rhythm and intensity.

Is There a “Normal” Way of Grieving?

People often ask what grief is “supposed” to look like, but there is no single typical pattern. Still, many people experience a mix of emotions such as shock, sadness, longing, or numbness after a loss. Over time, these feelings may shift as they adapt to life changed by the loss.

Anticipatory Grief

This type of grief occurs before the loss. It’s often in response to and preparation for an impending change.

Instances where anticipatory grief is common include when:

Their loved one has a terminal illness (or they’ve received a terminal diagnosis themselves)

They’re relocating to a new city and leaving their close friends behind

They’re planning a career shift and won’t spend their days working with the colleagues they’ve grown to admire

Sadness, anxiety, and uncertainty about the future can characterize anticipatory grief. Traditionally positive events like graduations, job promotions, and marriage can also precipitate these feelings. In these situations, anticipating the loss of familiar routines, relationships, interactions, places, and identities can cause grief.

Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD)

Prolonged Grief Disorder is a new diagnosis introduced in the DSM-5-TR (2022) to describe a pattern of persistent, impairing grief that extends beyond expected cultural and developmental norms.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2022), PGD is diagnosed when:

1. The loss occurred at least:

12 months ago for adults

6 months ago for children

2. The person experiences intense, persistent yearning or preoccupation with the deceased

This is the central feature of PGD.

3. In addition, at least three of the following are present nearly every day for at least the past month:

Difficulty accepting the death

Feeling that life is meaningless or empty without the person

Identity disturbance (feeling part of oneself has died)

Intense emotional pain such as sadness, guilt, anger, or bitterness

Emotional numbness

Avoidance of reminders of the loss

Difficulty reintegrating into daily life (e.g., social withdrawal, trouble engaging with work or activities)

A persistent sense of disbelief

Intense loneliness

4. These symptoms cause significant distress or impairment

This may affect social connection, work, home functioning, or general well-being.

5. The symptoms exceed cultural, religious, or age-appropriate expectations

PGD is a specific mental health condition marked by persistent, intense grief that interferes with daily life long after most people begin adapting to their loss. It is separate from depression or PTSD, although symptoms can overlap.

One unique aspect of the diagnosis is that these symptoms must exceed cultural, religious, or age-appropriate expectations. This highlights how grief is not a universally timed process. What is considered “prolonged” or “atypical” depends greatly on the cultural and social context surrounding the bereaved individual.

This criterion also underscores the need for clinicians to approach PGD with cultural humility and an understanding of what grief typically looks like within a person’s community, traditions, and developmental stage.

Supportive treatment may include grief-focused therapy, medication management for co-occurring symptoms, and integrative approaches that help stabilize sleep, energy, and emotional grounding.

How long does prolonged grief last?

There is no universal timeline for grief, and people adapt to loss in many different ways. Research shows that bereaved individuals tend to fall into distinct symptom patterns rather than a single predictable course. In a large study (Boelen, 2021) examining prolonged grief disorder (PGD), depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms, three subgroups emerged:

a group with low symptom levels,

a group with predominantly PGD symptoms, and

a group with high, comorbid symptoms.

Certain factors—such as a more recent loss, lower levels of education, the death of a partner, or an unexpected or violent death—were associated with more intense and persistent symptoms. The study also found that avoidance behaviors were strongest among those with the highest symptom levels.

These findings highlight that PGD is a distinct condition rather than simply “grief that lasts too long,” and that its duration depends on many personal and situational factors. Supportive, targeted treatment often focuses on helping reduce avoidance behaviors and supporting adaptation to the loss.

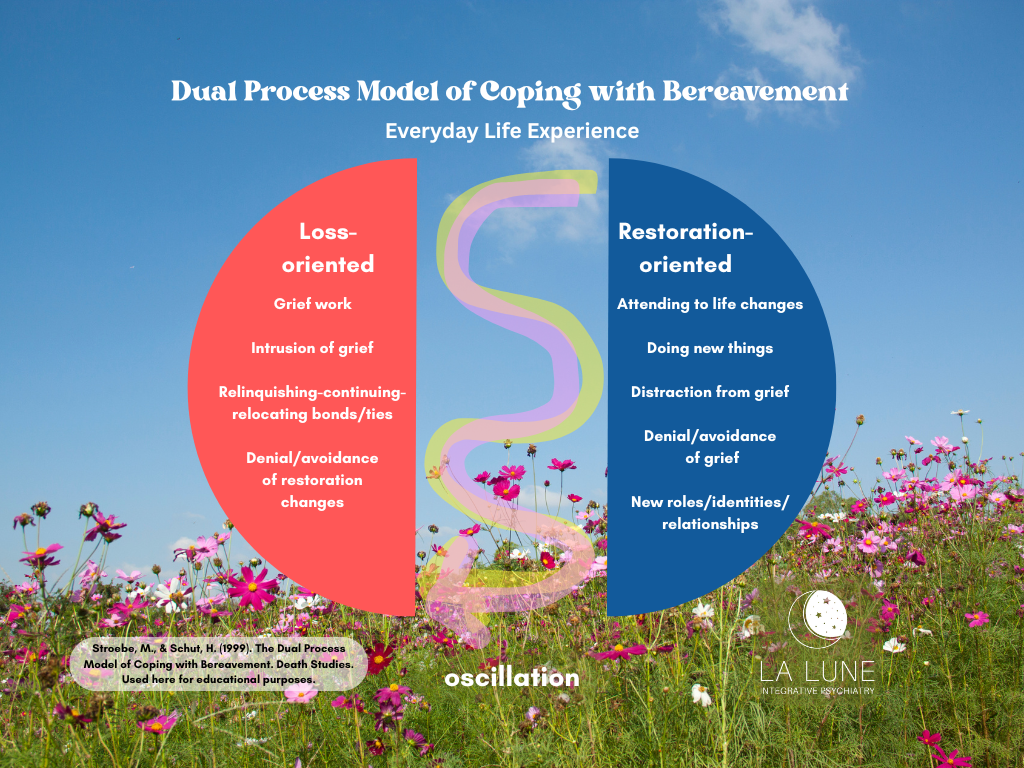

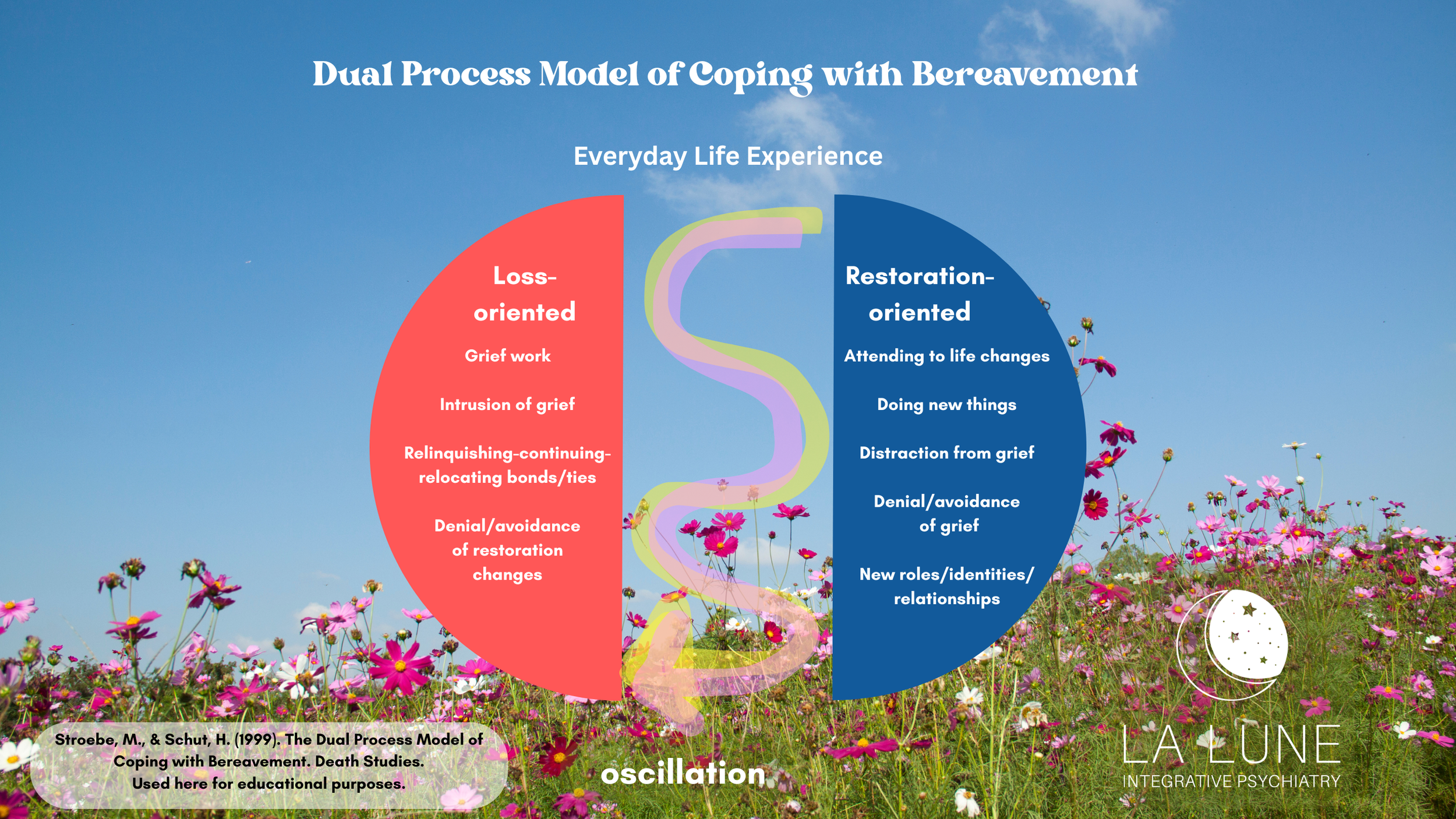

The Dual Process Model

Recovery from grief isn’t a straight upward path — it naturally moves in waves. You may revisit emotions you thought had settled or feel moments of relief followed by renewed sadness.

The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement (Stroebe & Schut, 1999) explains that healthy grieving involves oscillating between two modes:

Loss-oriented coping: confronting emotions and memories related to the loss

Restoration-oriented coping: focusing on daily life, new roles, and practical tasks

Rather than progressing in one direction, people move back and forth between these states. This oscillation helps them gradually adapt to both the emotional impact of the loss and the real-world changes that follow.

Navigating grief through integrative care

As grief impacts the whole person, healing must too. At La Lune Integrative Psychiatry, support may include:

Therapy to process emotions and find meaning

Medication management might be recommended when depression, anxiety, or insomnia interfere with recovery. Prescribers need to do a full psychiatric assessment to understand if medications can be helpful.

Lifestyle and nutritional guidance to support sleep, energy, and mood during periods of emotional strain.

Connection-building including relationships, creative rituals, mindfulness, or spiritual exploration—to foster grounding and resilience.

Grieving and healing aren’t races to the finish line. They’re personal journeys that require patience, compassion, and support.

When to seek help for grief

Consider reaching out if:

Grief feels as raw months later as it did at first

You’ve withdrawn from loved ones

You can’t sleep, eat, or function normally

You feel hopeless or see no future beyond the loss

Professional support can help you move from constant pain toward a softer, more livable kind of remembrance.

Beyond Grief

At La Lune Integrative Psychiatry, we meet you where you are, with empathy, evidence, and care for your whole self. Our board-certified providers in Arizona, Colorado, Oregon, Washington, and New Hampshire can draft a care plan that takes into account your whole story, following the threads of grief wherever they touch.

Together, we’ll help you navigate grief at your own pace, find steadier footing, and reconnect with meaning and possibility.

If you’re ready for support, reach out to La Lune Integrative Psychiatry to schedule an evaluation.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Boelen, P. A. (2021). Symptoms of prolonged grief disorder as per DSM-5-TR, posttraumatic stress, and depression: Latent classes and correlations with anxious and depressive avoidance. Psychiatry Research, 302, Article 114033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114033

Goodall, R., Krysinska, K., & Andriessen, K. (2022). Continuing bonds after loss by suicide: A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2021.1994299

O’Connor, M.-F., Wellisch, D. K., Stanton, A. L., Eisenberger, N. I., Irwin, M. R., & Lieberman, M. D. (2008). Craving love? Enduring grief activates brain’s reward center. NeuroImage, 42(3), 969–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.256

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

Tyrrell P, Harberger S, Siddiqui W. Kubler-Ross Stages of Dying and Subsequent Models of Grief(Archived) [Updated 2023 Feb 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507885/

Disclaimer: This website does not provide medical advice and may be out of date. The information, including but not limited to text, PDFs, graphics, images, and other material contained on this website are for general educational purposes only. No material on this site is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, and does not create a patient-doctor relationship. Always seek the advice of your qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition, lifestyle or dietary changes, treatments, and before undertaking a new health care regimen. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.